Three Must-Read Books To Get People Out of Their Comfort Zones and Spark Innovation

Recent works by Ward Farnsworth, Adam Grant and Hal B. Gregersen share unique perspectives on collaborative learning, creativity and discovery

In an increasingly illiberal and polarized world, how do we draw out the best from one another without devolving into hurt feelings and unproductive efforts? Our egos and foibles often get in the way of critical thinking and truth-seeking. People with different backgrounds and experiences have different ideas of the best way to get things done. No one person has the best answer every time. We all know from experience that collaboration can be bumpy, if not downright infuriating, because of, well, people.

Whether in the workplace or in our personal lives, discoveries and insights are more likely to happen when we are open to the perspectives of others. Easy to say, hard to do. But these three charming and insightful books can help us to pursue truth while navigating an increasingly chaotic world. The advice they propose can yield big payoffs by sparking personal growth, collaborative learning, creativity and discovery.

Generous Regard for Others

First, Ward Farnsworth’s “The Socratic Method: A Practitioner’s Handbook” makes the Socratic method come alive for modern times. In fact, it was the best book I read in 2022; I couldn’t put it down.

A legal scholar with a love of philosophy, Farnsworth challenges us to think about what gets in the way of truth-seeking: ego, stubbornness, wishful thinking, bias, dogmatism, partisanship, blind spots, assumptions, power dynamics and self-deception. It is all too easy to spot these tendencies in others, but if we’re being honest, these traits exist within ourselves too. Our natural foibles get in the way of learning and lead to bad decisions, wasted time, burned relationships or worse. Farnsworth presents the Socratic method as a tool to help us overcome these all-too-human tendencies.

The Socratic approach involves treating our discussion partners as dignified equals. Together we are stress-testing our thinking so we can see the situation or problem more clearly and arrive at the truth. There is a sense of empowerment, regard and respect. The Socratic method is the opposite of trying to win an argument or dunk on someone. “It means treating challenge and refutation as acts of friendship.”

If our conversation partners seem stubborn or dug in, the Socratic approach would have us courteously ask what might cause them to change their mind. Or if their arguments aren’t clear, we would then generously help them express their views more clearly, making the strongest case. This is the ultimate expression of respect for another person. In the Socratic approach, goodwill is at the heart of disagreement—it is far worse to hold false beliefs or be ridiculous without realizing it, far better to strive for what is true.

The further I read, the more I wanted to have a conversation over a beer with Socrates. He had a lively sense of humor, was self-deprecating and would often admit his own ignorance to coax others to explore a question with him. His two passions were the love of the truth and the well-being of others. For someone regarded as the father of Western philosophy who lived 2,500 years ago, he seems so modern, kind and relatable.

When you were young, your grandmother probably asked you, “If your friends would jump off a bridge, would you?” Likewise, Socrates had zero interest in what large numbers of people believed to be true. The Socratic “one-witness principle” means leaving peer pressure at the door and not caving to the pressures of tribe or horde mentality, especially bullies. The one-witness principle recognizes individual agency and freedom of conscience. The Socratic method involves confronting our own hidden assumptions, self-deceptions and inconsistencies; collective opinion has no place here. We ignore what “everyone says,” and instead, we explore the truth through one-on-one debate, while asking probing questions to ensure we aren’t talking past one another. Socrates would try to discover, what do you personally believe to be true and why?

Courage in the Face of Difficulty

Another fundamental aspect of the Socratic method is courage. Courageous questions are meant to bring what is hidden or unspoken out into the open. “One who says something shocking should be thanked for putting the claim on the table so that it can be rationally talked about and tested. The act of doing so is a personal risk taken in part for the good of the community.” Think about how much more productive this attitude would make our workplace meetings.

The Socratic approach leaves seniority or rank at the door. Rather, there is an emphasis on individual freedom of thought. Throughout a discussion, before assuming there is agreement with his discussion partner, Socrates checks in, asking, “Can we agree this is true?” He is checking for either consensus and buy-in, or additional points of disagreement to explore. Socrates aims to empower his discussion partners, which is quite radical. Perhaps the radical nature of the Socratic method is what ultimately got him into trouble with those in power in his day.

Farnsworth masterfully shows us how the Socratic method can help us today. It isn’t about what to think, but a technique for how to think. It requires a willingness to be uncomfortable, to admit what we don’t know and to ask hard questions.

Admitting what we don’t know is also a crucial component of Adam Grant’s book, “Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know.” Grant is an organizational psychologist at Wharton and a best-selling author. “Think Again” encourages us to beware of overconfidence and instead be open about what we don’t know.

Like Socrates, he invites us to laugh at ourselves, and the book is written in a spirit of playfulness. I found myself laughing out loud at a cartoon of a chicken seated at a desk with pen and paper, taking a narcissist test. The test instructions are: Step 1, take a moment to think about yourself. Step 2, if you made it to step 2, you are not a narcissist. Humorous quotes from pop culture underscore lessons. When discussing the pitfalls of overconfidence, he shares a quote from my all-time favorite TV comedy, “Frasier” (whose main character was lovably arrogant): “I have a degree from Harvard. Whenever I’m wrong, the world makes a little less sense.”

But Grant’s point is a serious one—that we often struggle with habits of overconfidence. He writes, “This book is an invitation to let go of knowledge and opinions that are no longer serving you well, and to anchor your sense of self in flexibility rather than consistency.” In other words, train yourself to think again.

It’s Okay To Be Uncomfortable

“Arguing was the family business,” Grant writes about the family of Orville and Wilbur Wright. From their earliest years, their father encouraged everyone in the family to read and debate. Though he was a bishop, their father would give his children books by atheists and then ask them what they thought. Lively family debates were encouraged. Through this atmosphere of thoughtful disagreement, the Wright children learned courage, humility and, importantly, how to gracefully lose an argument.

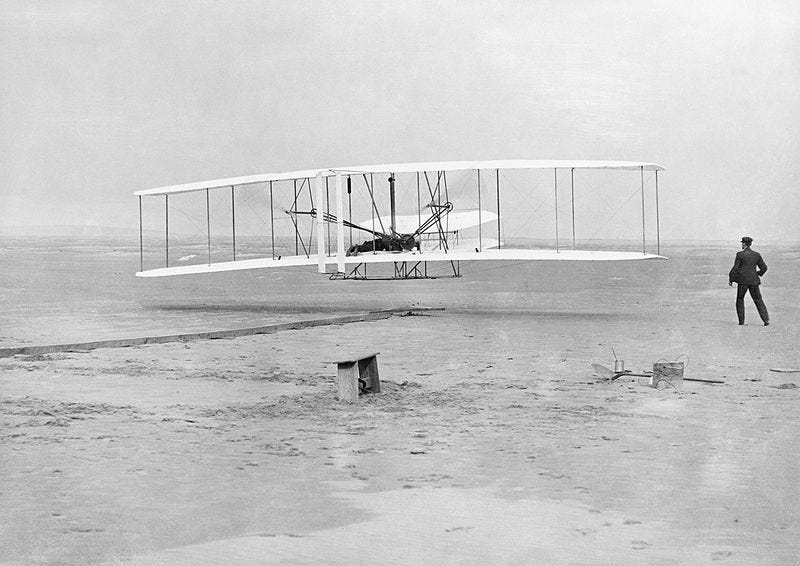

A love of debate was essential to the Wright brothers’ later discovery of flight. As they built components for their flying machine, at one point their work came to a standstill. They were stymied by the design for a propeller. They passionately disagreed with each other.

The feuding lasted for months as each took turns preaching the merits of his own solutions and prosecuting the other’s points. Eventually their younger sister, Katharine, threatened to leave the house if they didn’t stop fighting. They kept at it anyway, until one night it culminated in what might have been the loudest shouting match of their lives. Strangely, the next morning, they came into the shop and acted as if nothing had happened. They picked up the argument about the propeller right where they had left off—only now without the yelling. Soon they were both rethinking their assumptions and stumbling onto what would become one of their biggest breakthroughs.

The Wright brothers had come to realize they were both wrong, but they were both a little bit right, too. By hearing each other out, they found their breakthrough. They “figured out that their airplane didn’t need a propeller. It needed two propellers, spinning in opposite directions, to function like a rotating wing.”

The Wright brothers’ story illustrates the difference between relationship conflict and task conflict. Relationship conflict is a personal, emotional clash, perhaps even animosity, that can be painful and destructive. In contrast, task conflict is a difference of ideas or opinions and can be constructive. In the Wright brothers’ case, their task conflict led to a breakthrough that changed human history.

The Wright Flyer airborne during the first powered flight, Dec. 17, 1903. Orville is the pilot while Wilbur runs alongside. Image Credit: Imperial War Museums/Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately, many workplaces don’t encourage task conflict, according to Grant. Often, situations are dominated by what he calls the HIPPO—the HIghest Paid Person’s Opinion—rather than giving teams the freedom to constructively debate. The book shares cautionary tales as well as examples where organizations have found ways to overcome these institutional obstacles to collaborative learning and discovery. Throughout the book, Grant encourages us to be alert for overconfidence, conventional wisdom and deceptive data, to question what’s on the surface and what we think we know.

Creating Space for Questions

Hal Gregersen’s “Questions Are the Answer: A Breakthrough Approach to Your Most Vexing Problems at Work and in Life” also focuses on the importance of questions. Gregersen is a senior lecturer in leadership and innovation at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, a best-selling author and a consultant to organizations such as Disney and the World Economic Forum. His book is full of real-world stories of innovation from a variety of industries, for-profits and nonprofits, illustrating how asking the right questions brought about new and better ways of doing things, increasing team collaboration and creativity. His goal is to break us out of autopilot by training ourselves to ask rigorous questions, most especially of ourselves.

Pixar Animation Studios has earned 23 Academy Awards, and of the 50 highest-grossing animated films of all time, 15 of them are Pixar’s. Gregersen shares how Pixar teams are regularly expected to give “brutal” feedback to one another. A Pixar executive says that they assume, “early on, all of our movies suck,” and the job of the creative feedback process is to get the movie “from suck to not-suck.” Shocking, right?

But the Pixar executive explains, “Everyone in the room knows that the questions raised must be in the spirit of making the creative product as good as it can possibly be.” Without the manager setting the tone as a safe space, this kind of tough-love feedback process would never get off the ground. It’s about discovering better ways of doing things, creatively and collaboratively. I have seen this work well in post-project debriefs in my work as a nonprofit consultant.

Another technique from the book is brainstorming—for questions. If a team is hitting a wall, they can ask, “What are the questions we’d like to ask? Can we identify questions that, if answered eventually, would help us find our breakthrough?” At the first opportunity, I tried this in my workplace and found it to be quite helpful. I wrote about the experience in my new book, “Innovation for Social Change: How Wildly Successful Nonprofits Inspire and Deliver Results.”

A Little Help From Our Friends

Gregersen shares a scenario where an educator was invited to take on a new job as a college president. It was a tempting job offer. Adhering to the practices of his Quaker faith, he sought advice from his Quaker community. “I called on half a dozen trusted friends to help me discern my vocation by means of a ‘clearness committee,’ a process in which the group refrains from giving you advice but spends three hours asking you honest open questions to help you discover your own inner truth.” Much like Pixar, his friends asked hard questions. These questions surprised him and led him into deeper soul searching. Thanks to their questions he realized the “desire for the prestigious position had much more to do with my ego than with the ecology of my life.” He turned the lucrative position down and was happier for it.

Gregersen writes, “Questions have a curious power to unlock new insights and positive behavior change in every part of our lives. They can get people unstuck and open new directions for progress no matter what they are struggling with.”

These practices are important in our personal relationships and the larger world of politics and culture, and they are essential to the workplace as well. If we can’t productively engage with others to explore ideas, if we can’t risk admitting that sometimes we are wrong, we are stifling innovation and learning. We have a duty to speak up and seek out what works. Challenging the status quo will always involve facing hurdles and requires courage.

All three books help to model liberalism in the chaos of real life: Underlying each are the principles of the scientific method, pursuit of truth, bottom-up empowerment and freedom of thought and speech. Good ideas are worth fighting for. Life is too short, needs are too great and too much is at stake not to embrace viewpoint diversity and collaboration to explore ways to make the world a better place.

Original publication in Discourse Magazine in January, 2022.

Image credits: Unsplash, Sincerely Media